35624® – en unik probiotisk bakteriestam

Bakteriestammen Bifidobacterium longum 35624® är en unik probiotisk stam som isolerats från en frisk människas tjocktarm.

The [35624® culture] is a probiotic for which a beneficial effect for IBS symptoms has been shown in a high-quality, randomized, controlled trial.

Mayer E.A. (2008) Clinical practice. Irritable bowel syndrome. N Engl J Med 358, 1692-9.

35624®-stammen utvecklades som probiotika specifikt för IBS. Detta efter att en rad tester visat att just denna specifika bakteriestam hade potentiell effekt på IBS-symptom. Det har sedan gjorts två kliniska effektstudier med 35624® på personer med IBS:

En klinisk studie vid 20 primärvårdcentraler i Storbritannien, av Horwell et al. 2006

En klinisk studie vid 20 primärvårdcentraler i Storbritannien, av Horwell et al. 2006- En klinisk studie på Irland under ledning av Professor Eammon Quigley O’Mahony et al. 2005

Bakteriestammen Bifidobacterium longum1 35624®, har visat sig reducera symptomen på IBS (Irritable Bowel Syndrome), känslig tarm, som exempelvis uppblåsthet och gasbildning, magsmärtor, diarré och förstoppning. Dessa två studier har citerats mer än 1 000 gånger i vetenskapliga publikationer.

35624®-stammen är erkänd för sin höga evidensnivå när det gäller IBS. Denna bild förstärks av hög säkerhet, kvalitet och genomiska data, i tillägg till 20 års vetenskaplig forskning. De kliniska resultaten gällande 35624®-stammen har inkluderats i otaliga ”review-artiklar” och mer än 150 publikationer.

Forskningen bakom 35624®-stammen och information om IBS finner du här.

En lista med sökresultat för vetenskapliga artiklar med bifidobakteriestam 35624® och IBS hittar du här.

- bifidobacterium longum 35624 ibs – Search Results – PubMed (nih.gov)

- clinical studies bifidobacterium 35624 ibs – Google Scholar

1) Bifidobacterium longum 35624®-stammen var ursprungligen klassificerad och namngiven som Bifidobacterium infantis 35624® (Altmann et al. 2016), vilket är den benämning som förekommer i äldre studier och artiklar.

Mechanisms of the 35624® Strain

This unique Bifidobacterium longum probiotic strain is considered to have the best evidence base for efficacy in irritable bowel syndrome (IBS). The mechanisms underlying the efficacy of the 35624® culture in IBS have been extensively studied.

This research shows that the strain locks onto the irritated bowel to provide a calming and strengthening layer, thereby countering the impairment of gut barrier function that occurs in IBS and reducing IBS symptoms: bloating and gas, abdominal pain, and unpredictable diarrhoea and constipation.

The 35624® strain:

![]()

Arrives: Survives alive through the gut, reaching the intestines – the site of its activity.

![]()

Binds: Adheres to the intestinal epithelial cells and mucus layer of the gut barrier.

![]()

Calms: Reduces the disruption of the gut barrier that occurs in IBS.

Not all probiotics are alike. The affects are strain specific and potential health benefits can only be attributed to the strain tested.

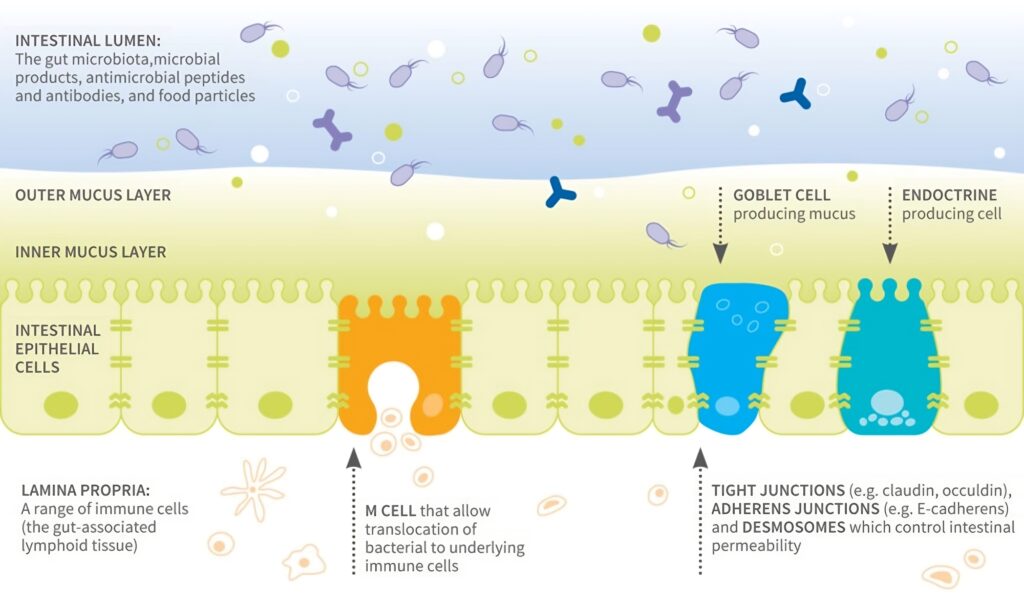

The Gut Barrier

This separates the gut lumen from the body’s internal environment. The gut barrier (Fig 1) is vital for maintaining intestinal homeostasis: it allows uptake of ions, nutrients and water into the body whilst restricting the entry of pathogens and harmful substances.3,7

Figure 1. Components of the gut barrier

Commensal Bacteria and Gut Barrier Function

Bacteria in the gut help maintain gut barrier function.17,27 Probiotic strains have also been shown to have direct effects on this.21 Evidence of the ability of bifidobacteria (including B. longum strains) to bind to the intestinal mucosa first came from in vitro tests using human intestinal cell lines that are validated models of the human colon: Caco-2 and the mucus-secreting HT29-MTX.2,8

Bifidobacteria have also been shown to adhere to mucus and inflamed mucosa.13,15,18,28 and can use host-derived mucins as growth substrates.26 A number of adhesion factors on the surface of bifidobacteria enable them to adhere to host structures.29

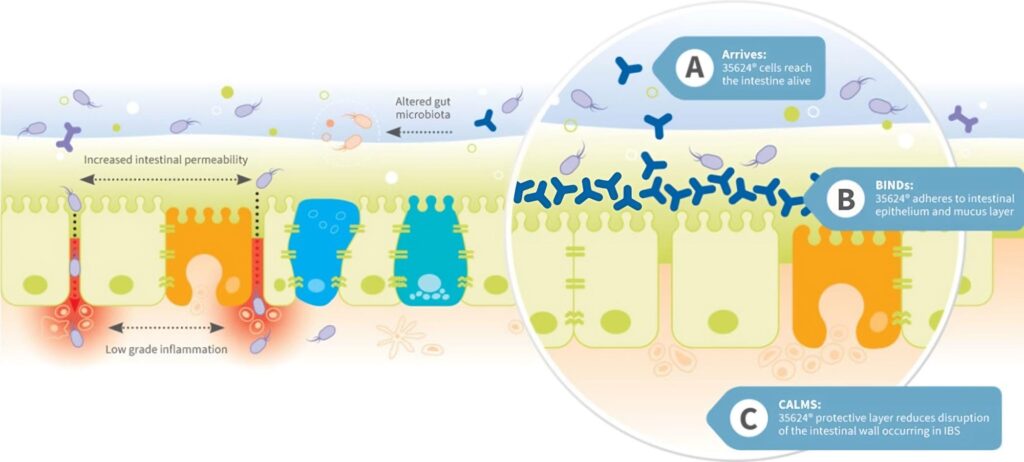

Impairment of the Gut Barrier in IBS

Loss of the integrity of the intestinal epithelium increases intestinal permeability (Fig 4a), which is seen in many IBS patients, particularly those with IBS-D. 3,19 Increased intestinal permeability (sometimes called ‘leaky gut syndrome’) has been linked to diarrhoea, low-grade inflammation and increasing severity of disease and visceral hypersensitivity in IBS. 4,11,12,19

Visceral hypersensitivity (a lower pain threshold) is observed in most IBS patients. 10 Compared to healthy people, patients experience more pain during episodes of bloating, flatulence or intestinal dysfunction, regardless of IBS subtype.

Certain IBS risk factors are also risks for intestinal dysbiosis (e.g. stress, dietary ingredients, antibiotics and infectious diarrhoea) and the profile of the faecal microbiota of people with IBS can differ from that of healthy people.11,25 Differences in the composition of mucosa-adherent bacteria have also been observed.22 In IBS, disruption of the gut microbiota composition contributes to the dysregulation of gut barrier function that occurs in this disease.22

Figure 4a. Impairment of the gut barrier in IBS and Figure 4b. Calming effect of the 35624® strain

The 35624® culture tackles symptoms of IBS by locking onto the irritated bowel and providing a calming and strengthening layer, countering the impairment of gut barrier function that occurs in IBS (Fig 4b) and reducing symptoms of bloating and gas, abdominal pain, and unpredictable diarrhoea and constipation. Key evidence for these effects are:

![]()

Arrives: Clinical trials showing survival of the 35624® strain through the gut.

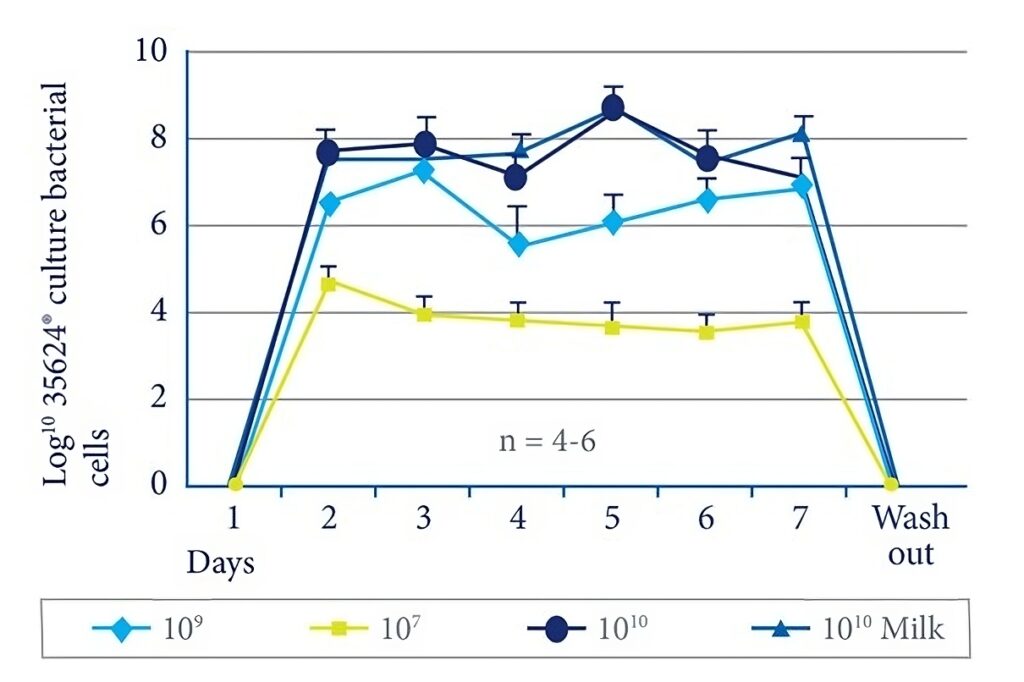

- Human intervention studies showing survival of 35624® through the gut (Fig 5).6,16,23,28 The strain was detected at levels up to 108 CFU/g in faeces.

- Production of an exopolysaccharide (EPS) layer, which helps protect the bacteria during transit through the gut to reach the colon alive and may contribute to gut barrier function.1,5

Figure 5. Survival of the 35624® culture through the gut.

References

1. Altmann F. et al. (2016) PLoS One 11(9), e0162983.

2. Bernet M.F. et al. (1993) Applied & Environmental Microbiology 59, 4121-8.

3. Bischoff S.C., et al. (2014) BMC Gastroenterology 14, 189.

4. Camilleri M. et al. (2012) American Journal of Physiology-Gastrointestinal & Liver Physiology 303, G775-G785.

5. Castro-Bravo N. et al. (2018) Frontiers in Microbiology 9, 2426.

6. Charbonneau D. et al. (2013). Gut Microbes 4, 201-211.

7. Chelakkot C. et al. (2018) Experimental & Molecular Medicine 50, 103.

8. Crociani J. et al. (1995) Letters in Applied Microbiology 21, 146-148.

9. Dunne C. et al. (1999) Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek 76(1-4), 279-92.

10. Farzaei M.H. et al. (2016) Journal of Neurogastroenterology & Motility 22, 558-574.

11. Foxx-Orenstein A.E. (2016) Therapeutic Advances in Gastroenterology 9, 354-375.

12. Fukui H. (2016) Inflammatory Intestinal Diseases 1, 135-145.

13. González-Rodriguez I. et al. (2012) Applied & Environmental Microbiology 78, 3992-3998.

14. Groeger D. (2018) GI adherence of Bifidobacterium infantis 35624 in vitro. PrecisionBiotics Internal Report.

15. He F. et al. (2001) Microbiology & Immunology 45, 259-262.

16. Healy S. et al. (2017) Gut 66, A25.

17. Hiipala K. et al. (2018) Nutrients 10, pii E988.

18. Izquierdo E. et al. (2008) Current Microbiology 56, 613-618.

19. Martinez C. et al. (2014) Gut & Liver 6, 305-315.

20. Mertz H. et al. (1999) American Journal of Gastroenterology 94,609-615.

21. Ohland C.L. & McNaughton W.K. (2010) American Journal of Physiology-Gastrointestinal & Liver Physiology 298, G807-G819.

22. Ohman L. et al. (2015) Nature Reviews in Gastroenterology & Hepatology 12, 36-49.

23. O’Mahony L. et al. (2005) Gastroenterology 128(3), 541-51.

24. Quigley E.M.M. et al. (2016) Journal of Clinical Gastroenterology 50, 704-713.

25. Quigley E.M.M. et al. (2018) Journal of Clinical Medicine 7, 6.

26. Tailford L.E. et al. (2015) Frontiers in Genetics 6, 81.

27. Ulluwishewa D. et al. (2011) Journal of Nutrition 141, 769-776.

28. Von Wright A. et al. (2002) International Dairy Journal 12,197-200.

29. Westermann C. et al. (2016) Frontiers in Microbiology 7, 1220.

30. Whorwell P.J. et al. (2006) American Journal of Gastroenterology 101, 1581-90.